Empiricism vs. Rationalism Part 1: Spinoza, Hume, and Ontology

Preface

I was looking through some of my old essays, and I found this piece I wrote about Spinoza’s and Hume’s ontological arguments. I found it interesting, so I thought I would post it with some edits.

Introduction

Philosophy is often considered to have four main branches: metaphysics, epistemology, axiology, and logic. This post will focus mostly on the first two branches, although it will also utilize principles from logic.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of knowledge. During the Enlightenment, two broadly defined epistemological schools of thought emerged: empiricism and rationalism. Empiricist, such as David Hume, believed that experience is required to understand the world. Conversely, Rationalists, including Spinoza, were united by a belief that knowledge of the world could be acquired through reason alone.

The branch of metaphysics studies the nature of reality, and ontology–a sub-branch of metaphysics–focuses on the nature of existence. In The Ethics, Spinoza attempts to utilize rationalist principles to develop his ontological theory of substance, which are things that are conceived through themselves and that make up reality. Foundational to Spinoza’s metaphysics is the logical necessity for a substance–namely God or Nature–that has infinite attributes, which are “that which the intellect perceives as constituting the essence of substance” (Spinoza 79). Spinoza presents three main arguments for God’s existence, but logical flaws and circular reasoning limit the validity of his conclusions. Furthermore, empiricists such as David Hume contest, with merit, the foundational supposition that rational arguments can reveal necessary truths about reality and existence.

Spinoza’s First Proof of God

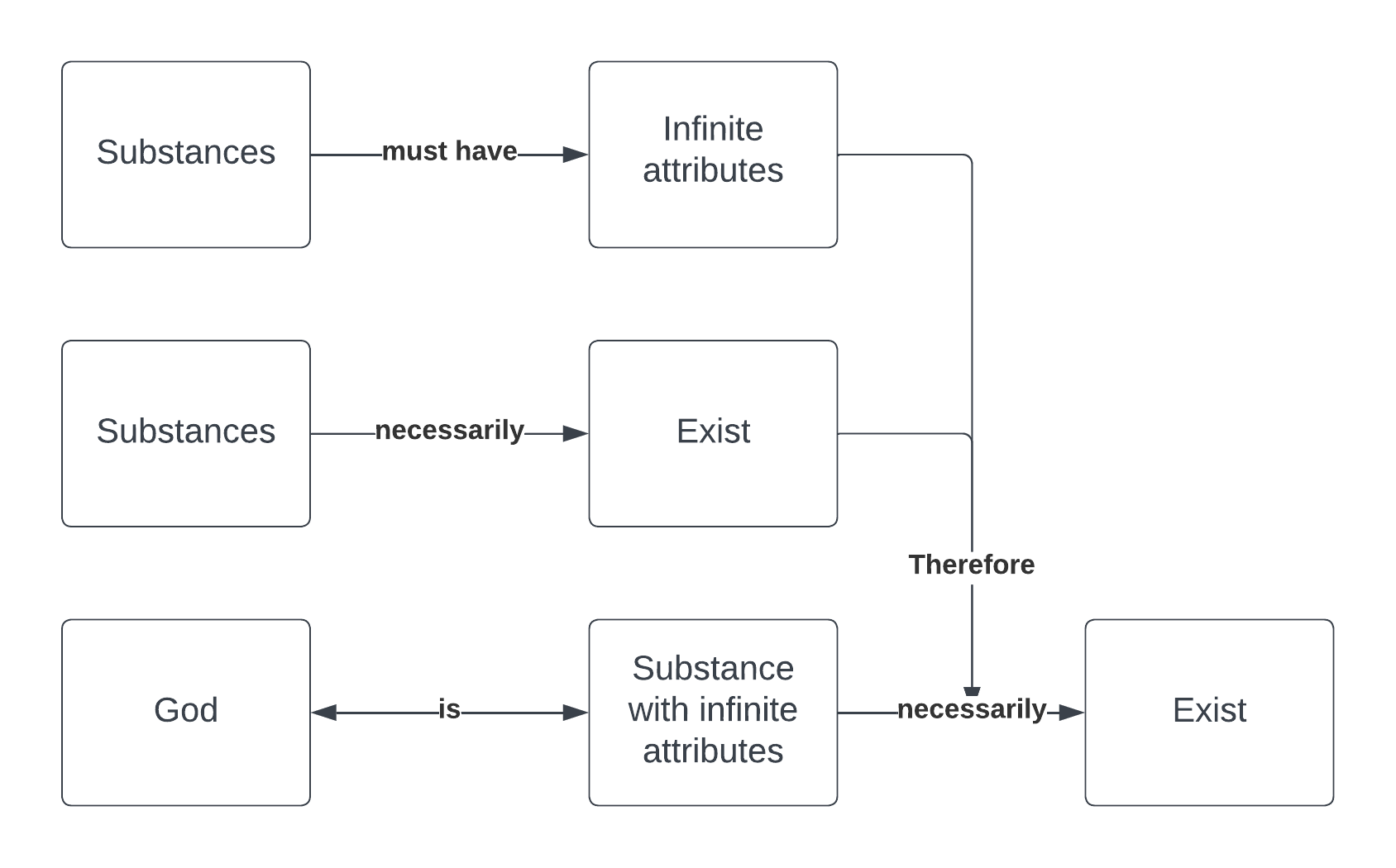

Spinoza’s first proof of God has three major parts. First, he defines God as a substance with infinite attributes. Next, he shows that substances necessarily exist. Finally, he demonstrates that substances are necessarily infinite. From these premises, he concludes that God, a substance with infinite attributes, necessarily exists. This general framework is summarized in the figure below.

Spinoza attempts to prove that substances necessarily exist because they must be their own cause. He starts by asserting that everything exists as either a substance or a modification of substance. Consequently, distinct things can only be differentiated by their substances’ attributes or their modifications. If substances are differentiated by attributes, then they cannot have the same attributes. If two substances are differentiated by their modifications, they still must have different attributes; “substance is… prior to its modification” (80), so the substances should be compared directly. Therefore, Spinoza concludes that no two distinct substances can have the same attribute. As a rationalist, Spinoza believes as an a priori truth that necessary and logical connections link cause and effect. Two substances with no shared attributes can have nothing in common and cannot have a causal relationship. Thus, the only alternative is that substances must be caused by themselves and so must necessarily exist.

Two main issues minimize the validity of Spinoza’s explanations. First, Spinoza’s arguments are circular. If one examines only the first axiom and the conclusion, Spinoza’s reasoning is reduced to “substances necessarily exist because everything that exists is a substance or made from substance.” The initial premise already assumes the existence of substance. Other parts of his argument also contain this assumption. For example, Spinoza asserts that either substances are caused by themselves or they are caused by other substances, neglecting the possibility that they are caused by nothing if they do not exist.

The second main logical flaw lies in his argument that distinguishable substances cannot share attributes. However, if substances have multiple attributes, then they can share attributes while still being distinguishable if their complete sets of attributes are not identical. For example, two triangles can be identical in shape but vary in color while still being distinguishable. Thus, even within his flawed circular framework, substances can cause other substances.

As a short aside, Gottfried Leibniz, another rationalist philosopher, agrees with these objections. Although Leibniz also believes in the existence of substances, substances in his framework can cause other substances; more specifically, a God substance creates all other substances and endows them with a part of its perfection.

Spinoza’s proof of substances’ infinitude contains similar issues to his argument for substances’ existence, and his concept of infinity is logically flawed. Spinoza starts his argument by defining something to be finite when “it can be limited by another thing of the same nature” (79). For example, a physical object is finite because a larger object can be conceived. Substances, which exist necessarily, either exist finitely or infinitely. If a substance is finite, then it is limited by another substance of the same nature, which must necessarily exist. This is a logical impossibility according to Spinoza because substances cannot share attributes. Consequently, substances must be infinite. The argument relies on the same flawed premises discussed earlier; he fails the convincingly demonstrate the impossibility for two substances to share attributes and the necessity for substances to exist. In addition to these recurring issues, Spinoza’s concept of infinity is incorrect. Sets usually considered infinite are finite based on Spinoza’s definition. For example, the set of natural numbers would be considered finite because the set of real numbers is larger. Therefore, the only infinity considered to be truly infinite under Spinoza’s paradigm is absolute infinity, or the greatest infinity. However, much as there is no absolutely largest real number, there is no absolutely greatest infinity—a larger infinity can always be conceived. Thus, in his framework, everything, including substance, must necessarily be finite.

Spinoza’s Second Proof of God

Infinity is central to Spinoza’s second proof of God. In the first premise of his argument, he proposes three possibilities regarding existence:

- Only finite beings exist

- Nothing exists

- Absolutely infinite and finite beings both exist.

If only finite beings exist, then finite beings have more power—or “potentiality of existence” (82)—than absolutely infinite beings. Spinoza believes this is a contradiction and an absurdity. Thus, possibility 1 is eliminated. The existence of nothing cannot be true either because he previously proved that substances necessarily exist, eliminating possibility 2. Thus, possibility 3 must be true; absolutely infinite beings must exist.

As previously demonstrated, an absolutely infinite substance or being is impossible if Spinoza’s definition of infinity is applied correctly, so the correct first premise should only have two possibilities: either only finite beings exist, or nothing exists. Furthermore, Spinoza’s assertion that finite beings cannot be the only things that exist is circular. Simplified, his argument is absolutely infinite beings must exist if finite beings exist because absolutely infinite beings have more potentiality of existence than finite beings. There is not an intuitively or demonstratively certain first principle; one could just as easily say absolutely infinite beings cannot exist because absolutely infinite beings have less potentiality of existence than finite beings.

Spinoza’s Third Proof of God

Spinoza’s third proof of God depends on the Principle of Sufficient Reason, which states that everything has a cause or reason. Thus, everything must have a cause for its existence or non-existence, and a thing necessarily exists if nothing prevents its existence. Spinoza then creates another disjunctive syllogism by again proposing 3 possibilities:

- God exists

- God does not exist because of a reason from within God’s nature

- God does not exist because of a reason from outside God’s nature

God is absolutely infinite and supremely perfect, so a cause for nonexistence cannot come from God. The reason for God’s nonexistence cannot be external to God either because God is a substance, and substances cannot cause other substances. Therefore, God must exist.

As in previous arguments, the premise that substance cannot cause another substance is not well-supported. Spinoza also derives the premise that a substance cannot be the cause of another substance’s nonexistence from the premise that a substance cannot be the cause of another substance’s existence. The logical connection between these two ideas is weak and is contradicted elsewhere in his arguments. For example, by asserting that substances cannot share a single attribute, he also implies that a single substance with a certain attribute then necessarily is the reason for the nonexistence of another substance with the same attribute. Finally, Spinoza’s arguments are again circular. To be absolutely infinite and supremely perfect, God must exist, yet God exists because he is absolutely infinite and supremely perfect.

David Hume’s Anti-Rationalist Arguments

David Hume, an Empiricist, attacks the rational basis underlying all of Spinoza’s arguments. In his namesake fork, Hume divides all knowledge into two categories: relations of ideas and matters of fact. Relations of ideas are a priori and can be demonstratively proven. The contrary or inverse of a relation of ideas is a contradiction. Matters of fact are not a priori and cannot be proven. Instead, they are grounded in experience, and their contrary does not imply a contradiction. All of Spinoza’s arguments are relations of ideas because he is trying to prove God’s existence without relying on experience. Notably, Hume asserts that relations of ideas do not necessarily have any validity in the real world; geometric theories about triangles can still be true even though a perfect triangle does not exist in nature. In the same way, substance does not exist just because the idea of existence is contained within the idea of a substance. Thus, even if Spinoza’s logical arguments were airtight, they would still be unable to prove the true existence of God.

Hume also argues against the validity of using causation in rational arguments. The Principle of Sufficient Reason, Hume argues, cannot be used to understand relations of ideas because causation is a matter of fact; they “are discoverable, not by reason but by experience” (Hume 256). People see that certain events consistently follow other events and label this tendency causality. The contrary to causality is not a contradiction, and not everything must have a cause. Thus, when Spinoza asserts that substances must be caused by themselves or another substance, he misses the possibility that substances exist but do not have a cause. Similarly, he also fails to consider the possibility that a thing can be nonexistent for no reason. Finally, Hume contends that because causality is not a logical necessity, there is no logical connection between cause and effect, invalidating Spinoza’s belief that things with nothing in common cannot cause one another.

Final Thoughts

The existence of an absolutely infinite God is the basis of Spinoza’s monist metaphysics and ethical philosophy. Not only does God exist, but God is also the only substance. Spinoza argues that if another substance existed, it would share an attribute with God because God is absolutely infinite. Since two substances cannot share the same attribute, no substance other than God can exist. Because of his monism, Spinoza believes the mind and body are two different expressions of a single deterministic substance, thus making free will impossible. Consequently, he advances an ethical philosophy centered around understanding the totality of nature, including how necessary emotions affect our mental well-being. However, his philosophy rests on unsteady grounds; his proofs of God’s existence as an absolutely infinite substance are unsound due to logical flaws, circular reasoning, and an absence of any connections to experience.

References

Hume, David. “An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding.” 17th and 18th Century Philosophy, edited by Brian Tapia, Cognella, San Diego, 250-287.

Spinoza, Baruch. “The Ethics.” 17th and 18th Century Philosophy, edited by Brian Tapia, Cognella, San Diego, 75-114.